As front-end developers, we’re used to thinking about what our code does. But increasingly, where it runs is just as important. Serverless and edge computing give us new options for putting logic closer to our users, but choosing the right location isn’t always obvious.

Should you personalise content at the edge? Can you run serverless functions for everything? When is a plain CDN enough? And when do you still need a good old-fashioned server?

In this post, I’ll break down how to choose where different parts of your application should run and how to factor in performance, scalability and vendor lock-in. I’ll share how we at De Voorhoede help clients map features to infrastructure, and how to avoid common mistakes when adding modern tooling to existing systems.

You can’t put a supercomputer in everyone's pocket

I love modern tech, and at De Voorhoede, we enjoy pioneering with it. But in everything we build, we try to put the user first. And our users? They don’t care what technology we chose or where our code runs. They just want a fast, smooth, and personalised experience.

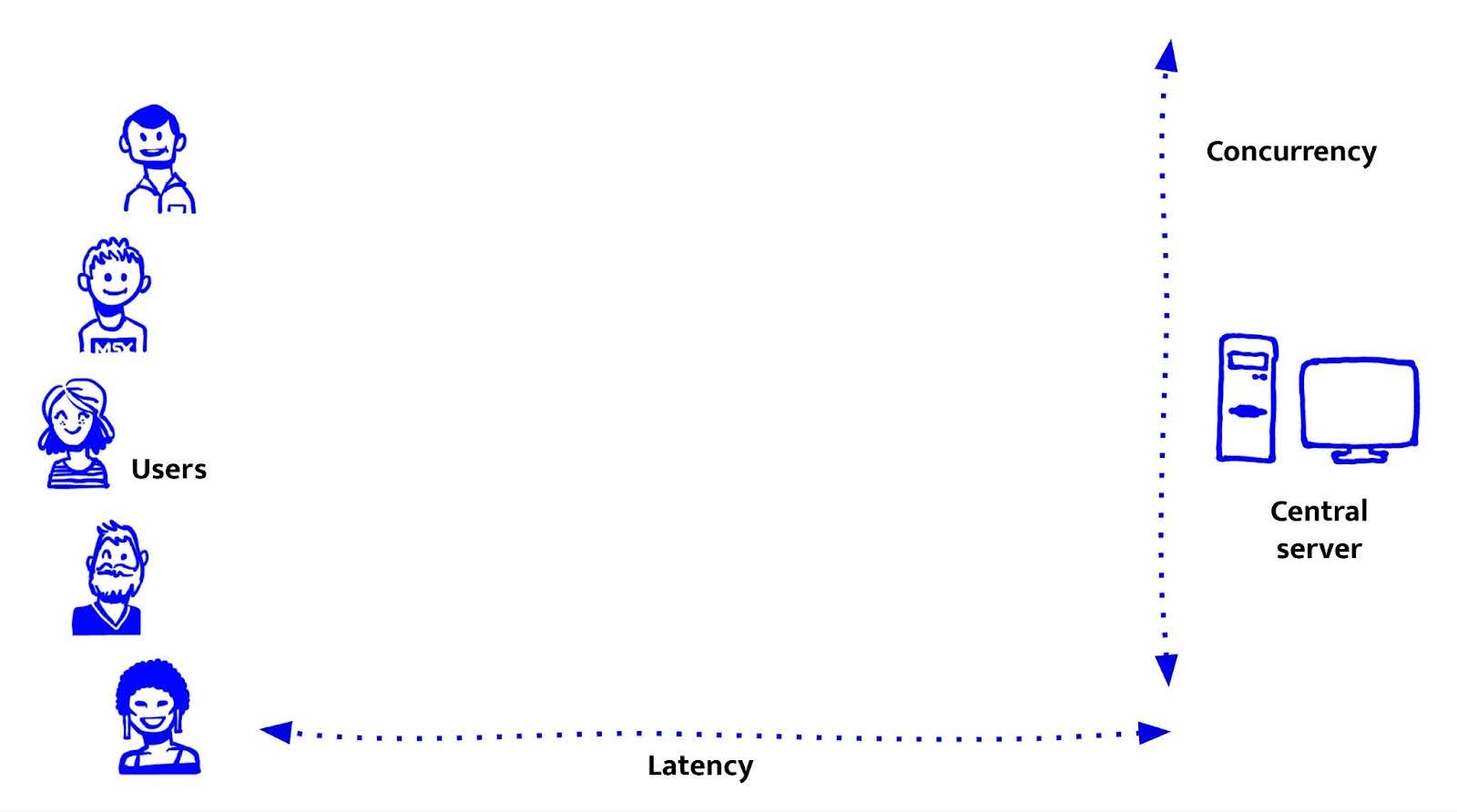

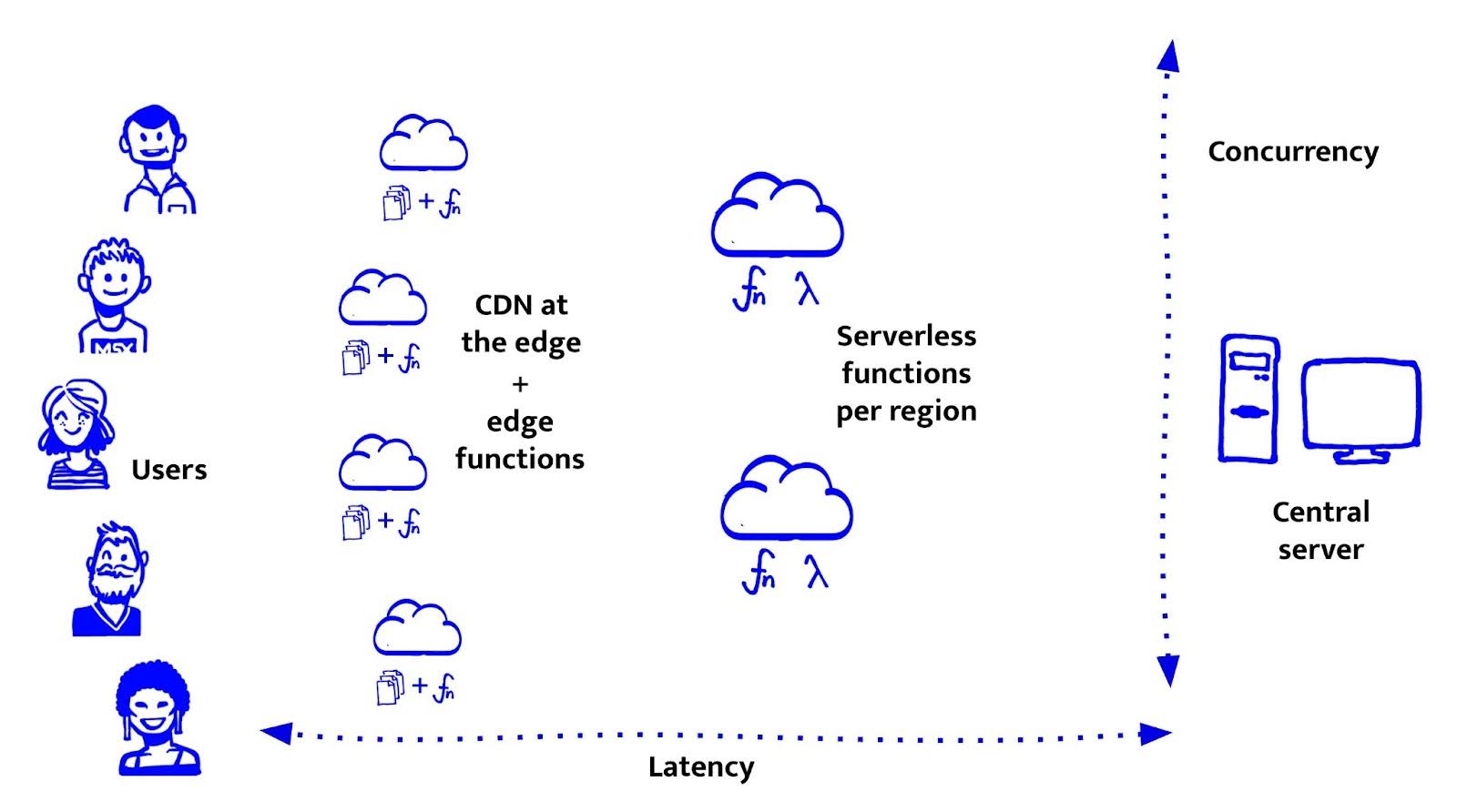

It’s tempting to assume that the closer to the user your code runs, the faster things will feel. And in many cases, that’s true. Reducing latency - the round-trip time from user interaction, to code execution, to UI update - can make a huge difference.

But performance isn't just about distance. It’s also about capability, what the hardware can actually handle once the request arrives.

On the client-side, we have no control over the user's device. It might be a brand-new iPhone, or a 6-year-old Android with a dozen tabs open. In contrast, on the server-side, we have full control. We can choose machines with more CPU power, memory, and even GPU acceleration.

The ideal setup, low latency and high capability, sounds great in theory. But in practice, putting powerful servers near every user just isn’t realistic. It’s expensive, hard to scale, and frankly, overkill for most use cases. You don’t need a supercomputer at the edge to show someone their name.

So when we architect an application, we’re constantly balancing latency against capability. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. It depends on what each feature needs. Let’s look at the options - and what they’re good (and bad) at.

Centralised servers: everything in one place

Before we had edge runtimes, serverless functions, and global CDNs, most web applications simply ran on a central server. And to be fair, many still do.

A centralised server gives you everything in one place: compute, file storage, and database access. Your back-end logic, front-end templates, static assets, and database connections all live together. Easy to reason about. Easy to control. When Node.js - a JavaScript server runtime - was introduced, centralised servers became part of our territory at De Voorhoede.

These days, containers are often used to run central servers. Tools like Docker and Kubernetes make it easier to deploy consistent environments, scale workloads, and move between cloud providers. But the architecture remains largely the same: user requests go to a central location, where everything happens.

This model still makes sense in many situations:

- Your users are located close to the server (for example, a Dutch company serving Dutch users).

- Your traffic is predictable enough to size your server accordingly.

- You want full control over your runtime and environment.

- You’re hosting an application with complex compute needs or dependencies that don’t play well with distributed runtimes.

But it’s not without trade-offs:

- Latency: Users far from that data centre feel it. No matter how much you optimise your code, network distance adds unavoidable delay.

- Concurrency: A single server has finite resources. Scaling for sudden traffic spikes often requires over-provisioning, or getting into more complex orchestration.

- Flexibility is limited: every feature has to live on the same server, or you start introducing service sprawl.

And of course, we’re glossing over databases here, a big topic in itself. For now, let’s just say that central servers often sit close to the database for good reasons: low-latency access, persistent connections, and predictable performance. But that also tethers them to one location.

In short, a central server gives you a lot of power and simplicity, but only if your application's needs, users, and traffic patterns align with that central point. Next, let’s look at what happens when we start distributing things, first with CDNs.

CDNs, the first edge: static files closer to the user

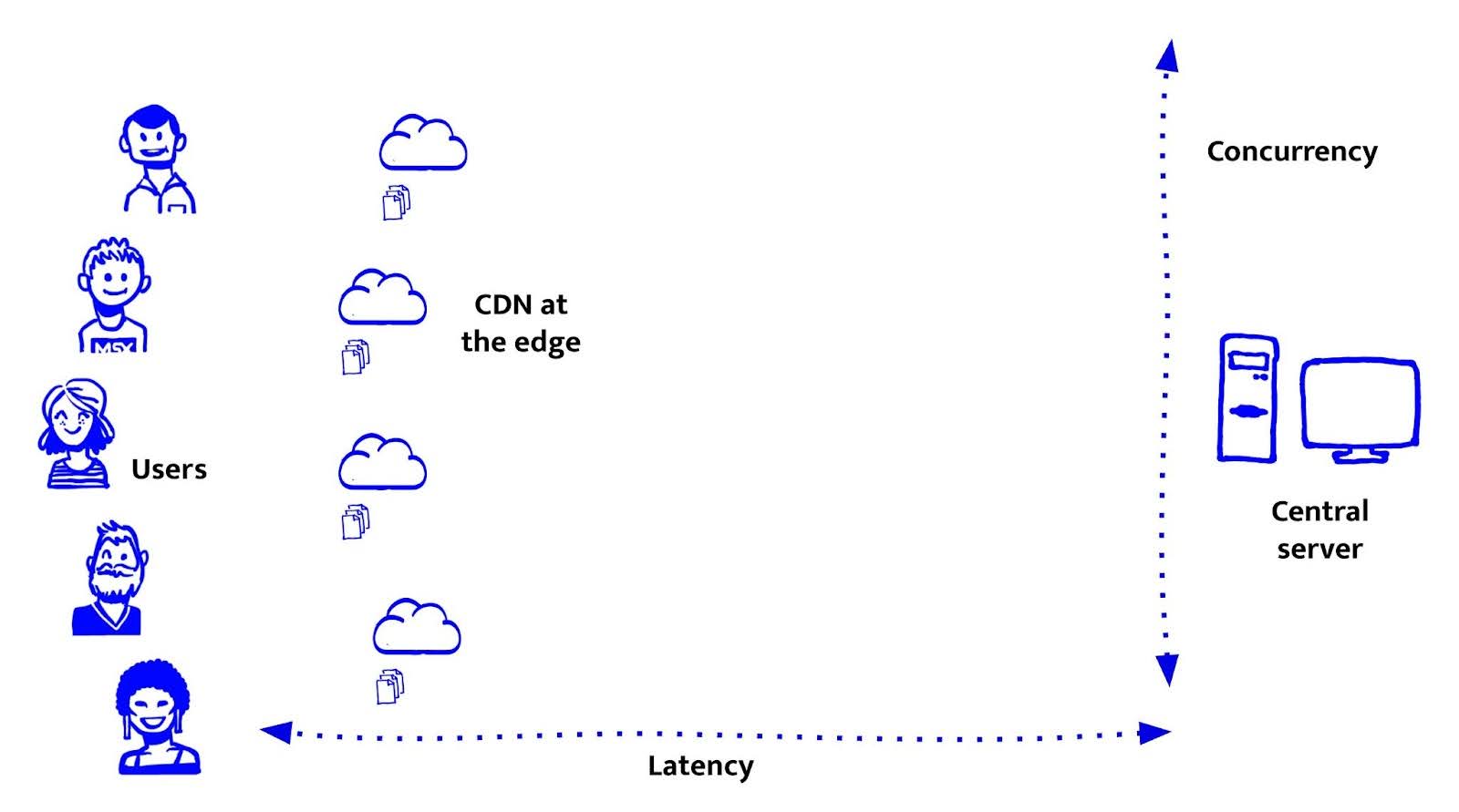

CDNs were the first big step toward bringing the web closer to the user, but only for static assets. They dramatically reduce latency and offload work from origin servers, but they’re also limited: they can’t run logic or access data. Understanding what CDNs are good at (and not) is key for deciding where to place front-end features.

What CDNs do well is straightforward: they serve static files, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images, from servers physically closer to the user. That reduces latency and bandwidth costs, and helps scale effortlessly to a global audience without spinning up more infrastructure.

For us at De Voorhoede, CDNs really started to shine with the rise of the JAMstack. Pre-rendered HTML, deployed to a CDN, made sites blazingly fast and cheap to host. Thank you Netlify It also opened the door to headless architectures, separating the front-end from CMSs, commerce engines, and back-end systems. That gave us a huge advantage: we could iterate on the front-end independently. Preview environments became the norm. Instead of maintaining one acceptance and one production server, we had a fresh deploy for every pull request. It was fast, simple, and empowering.

But CDNs can only take you so far. A CDN is essentially a server-side cache, great for performance, but not for flexibility. It requires thoughtful invalidation strategies, whether time-based (max-age, stale-while-revalidate), tag-based (like Fastly’s Surrogate Keys or Cloudflare’s Cache Tags), or manual purging. And ultimately, the cache is shared: it can’t personalise, run logic, or respond to user-specific state. For anything dynamic, like authenticated content, A/B testing, or per-user rendering, you either fall back to client-side workarounds or hit your origin server again.

So how do we bring compute closer to the user?

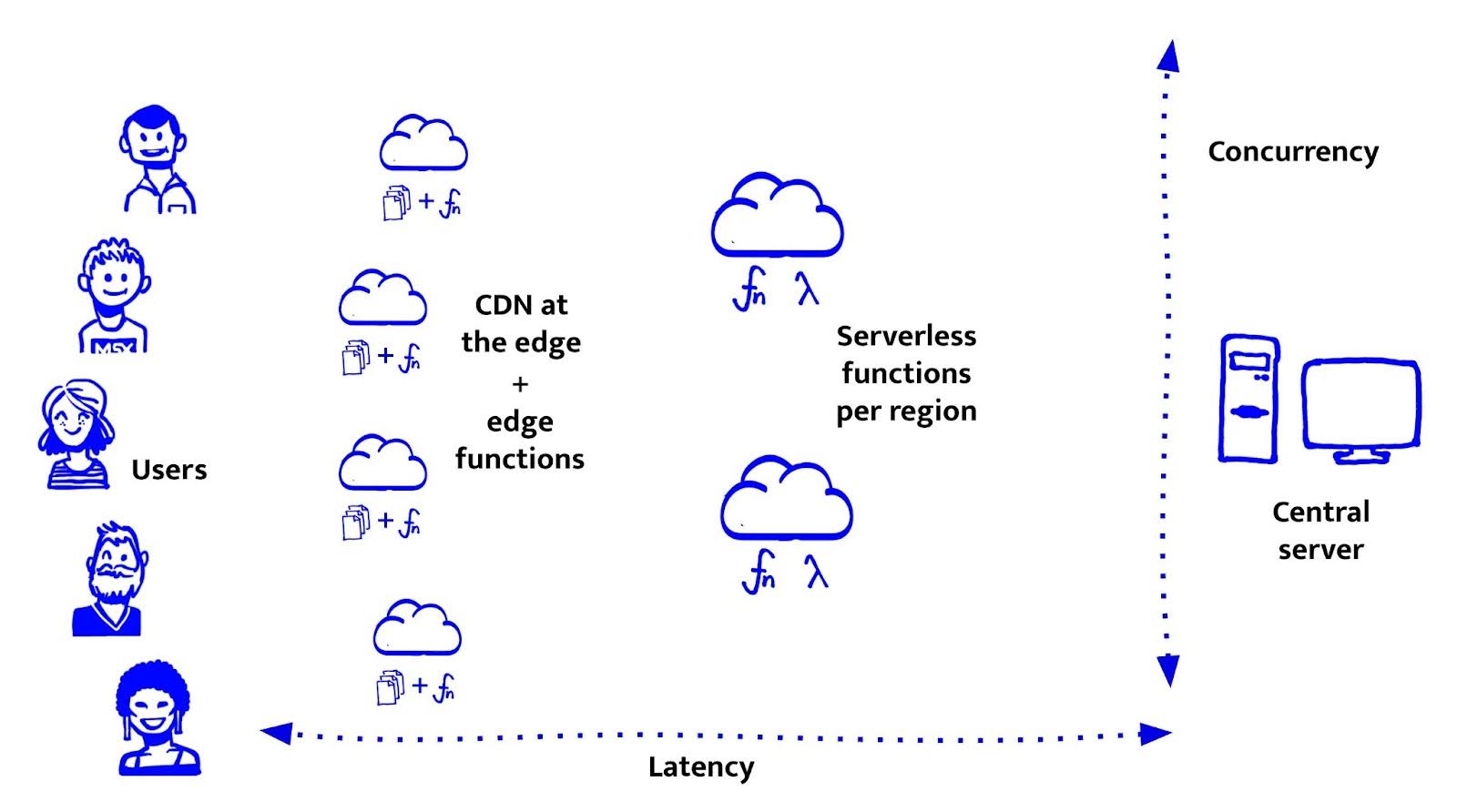

Serverless functions – compute getting closer

Serverless functions, like AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Functions, bring compute closer to the user. Not quite to the edge, but to regional servers (like eu-central-1 or us-west-2). So closer than centralised servers and more dynamic than a CDN.

They’re flexible and easy to use: just deploy a function, and it runs when needed, whether once or a million times. They scale automatically, you don’t pay for idle time, and they’re great for simple API integrations.

Most providers support multiple languages, including JavaScript (Node.js). That made serverless a natural fit for us at De Voorhoede. We could stay in JavaScript, write backend logic like form handlers or CMS webhooks, and deploy it right alongside the front-end.

But serverless has trade-offs.

- Stateless by design: each function call starts fresh, no in-memory state, no persistent connections. That’s fine for lightweight logic, but starts to hurt as things grow.

- Cold starts: functions that haven’t been used in a while take longer to respond. Cold starts can range from a few hundred milliseconds to several seconds, depending on the platform and size of your code.

- Not all packages play nice: while Node.js is supported, some libraries (like those with native dependencies or file system access) don’t work well. Larger packages slow things down, try running Prisma with GraphQL and you’ll feel it.

- Platform-specific function APIs: each provider has its own way of handling requests and responses. Abstractions like the Serverless Framework can help, but add complexity and vendor coupling.

Serverless is a great step toward modular, scalable infrastructure. But if we want even faster response times and logic that runs right at the edge, there’s one step closer to the user: edge functions.

Edge functions - compute at your doorstep

With edge functions, we can finally run dynamic logic as close to the user as it gets, short of running on their device. These functions execute code right where our static files already live: at global edge locations. They’re ideal for lightweight, latency-critical tasks like authentication, A/B testing, rewrites, and simple API integrations.

Unlike serverless functions, edge functions don’t run in full containers or VMs. Instead, they use isolates, a lightweight, sandboxed environment built for speed and scale. They offer ultra-low latency and near-zero cold starts, but come with tight resource limits and no access to many Node.js features that typical packages depend on.

Notable runtimes include Cloudflare Workers, Deno Deploy, and (to some extent) Bun. As with serverless platforms, each has its own APIs and quirks. That makes code portability a challenge. Fortunately, the WinterCG group is working to standardise web APIs across runtimes, so we can write portable, web-native JavaScript that works anywhere. Meanwhile, the UnJS community is building tiny, runtime-agnostic utilities like unenv, h3, and unstorage, modules designed to “just work” across environments.

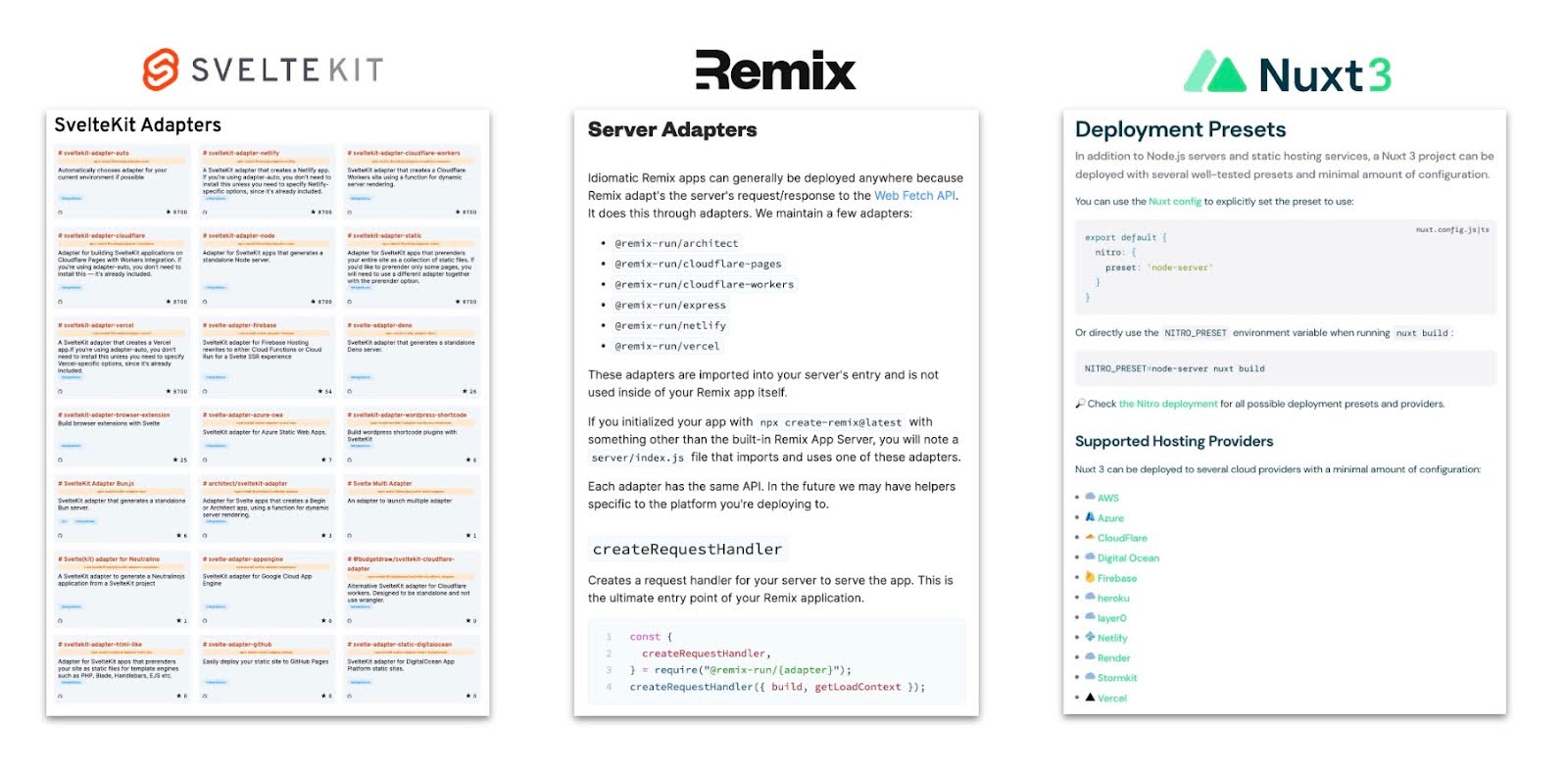

Frameworks play a key role in completing this universal developer experience. Astro, SvelteKit, Remix, and Nuxt 3+ all offer runtime adapters that let you target edge platforms without changing your code. These adapters compile your app to match the chosen runtime, abstracting away environment-specific details while keeping the final output lean and performant. The notable exception is Next.js, which, despite being open source, is deeply tied to Vercel’s platform and difficult to run fully elsewhere.

So, how close should your code be?

It turns out the answer is simple: as close to the user as possible, using just enough power for the job.

In real estate, there’s a saying: location, location, location. The same applies to your application logic. The closer you place your code to the user, the faster and more responsive your experience will feel. But that speed comes with trade-offs. Edge runtimes are fast, but limited. Serverless adds flexibility, but at a cost. Central servers give you control, but only if your users can wait for it.

Putting it all together:

| Criteria |

Static CDN |

Edge Function (e.g. Workers) |

Regional Serverless |

Centralised Server |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency (close to user) | ✅ | ✅ |

⚠️ (region-based) |

❌ |

| Concurrency (auto-scaling & volume) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ⚠️ (requires scaling infra) |

|

Dynamic logic |

❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

|

Cold starts |

❌ |

✅ (near-zero) | ❌ (can be slow) | ✅ |

|

Heavy computation |

❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

|

Portability (no vendor-lock) |

✅ | ⚠️ (runtime-specific) | ⚠️ (platform-specific) | ✅ |

|

Best for |

Static sites, assets |

APIs, personalised UIs, A/B tests, auth |

APIs, light server logic |

Monoliths, legacy systems |

At De Voorhoede, we start by asking: What’s the least powerful, closest option that can handle this part of the job?

- If it can be static, we pre-render and cache it.

- If it needs lightweight logic, we run it at the edge.

- Only when something needs more compute or persistent connections do we fall back to serverless or central servers.

The modern front-end isn’t just about what you build, but where you run it. And with today’s tooling, we can choose with more precision than ever.