Most of the internet is written in English, and as Western developers, we tend to build with Latin-based scripts in mind. But what happens when we need to create interfaces for Non-latin writing scripts?

After earning a BA in Japanese linguistics, I began my front-end career in Tokyo, building multi-lingual web solutions in Japanese and English. Now back in my home country and working at de Voorhoede, I’ve noticed some specific CSS/ HTML techniques required for non-Latin scripts that I don’t use as often anymore but remain essential knowledge.

While my personal experience is rooted in Japanese, at de Voorhoede we’ve also built interfaces for right-to-left non-Latin scripts, giving us a broader perspective on multilingual accessibility.

In this post, I’ll share practical tips for building web solutions that support non-Latin scripts. Most of the examples will be drawn from my experience with Japanese, but the overall message is applicable for any non-Latin language on the web!

The hidden bias of the Latin script

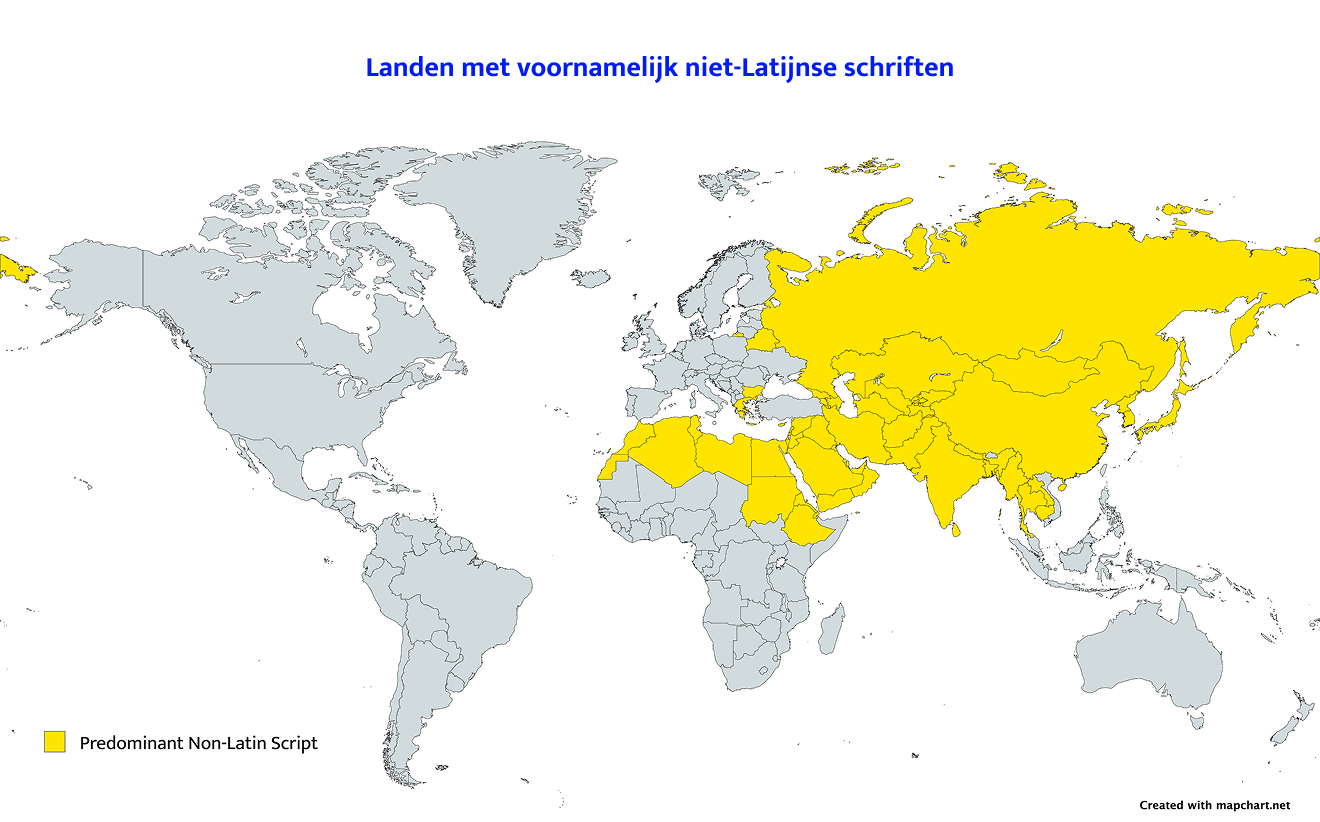

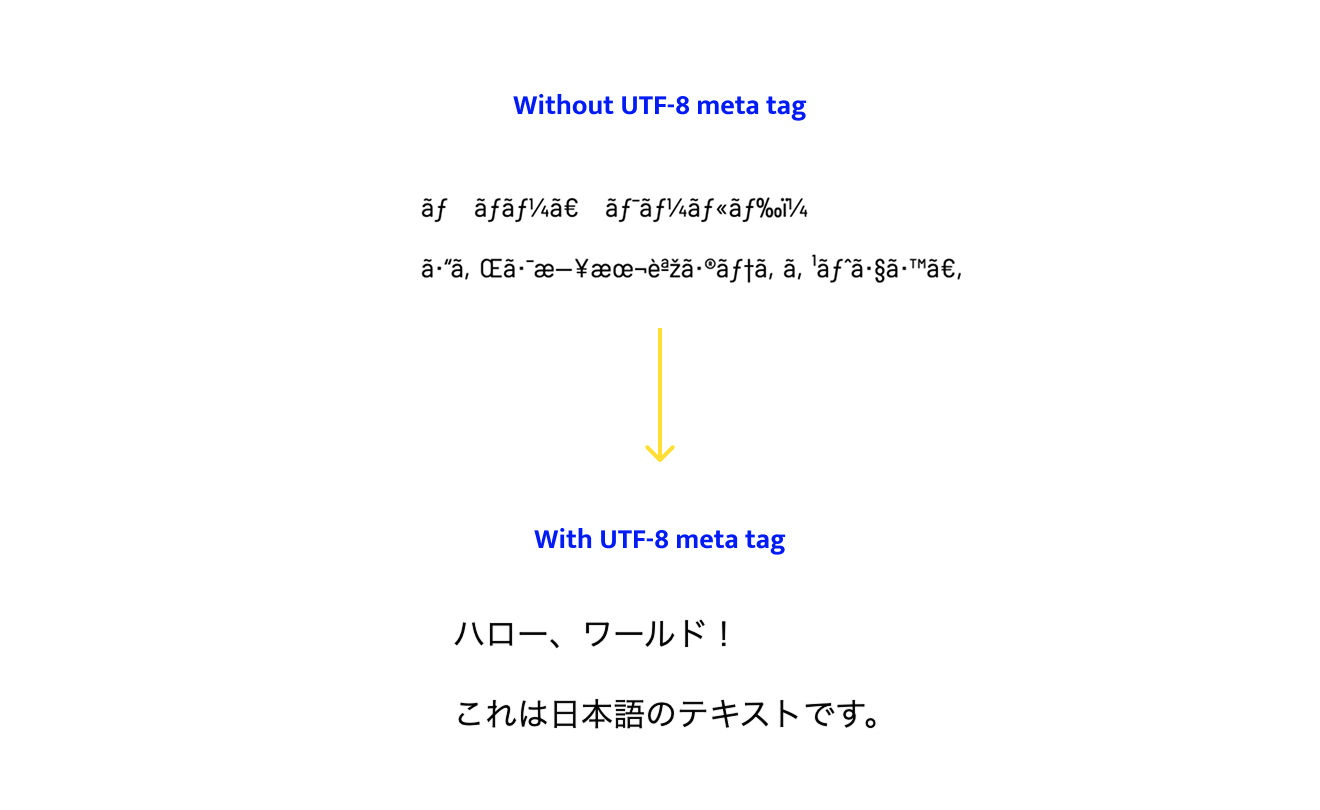

There are over 50 countries worldwide that predominantly use non-Latin scripts. Despite this, the web was built with English in mind, and most defaults still reflect that. For example, without <meta charset="UTF-8">, non-Latin characters may not render at all. This is because the default of ASCII only supports Latin characters.

While this post focuses on CSS and HTML, it’s worth remembering that Latin scripts enjoy an unfair advantage of being the default on the web.

Generic font

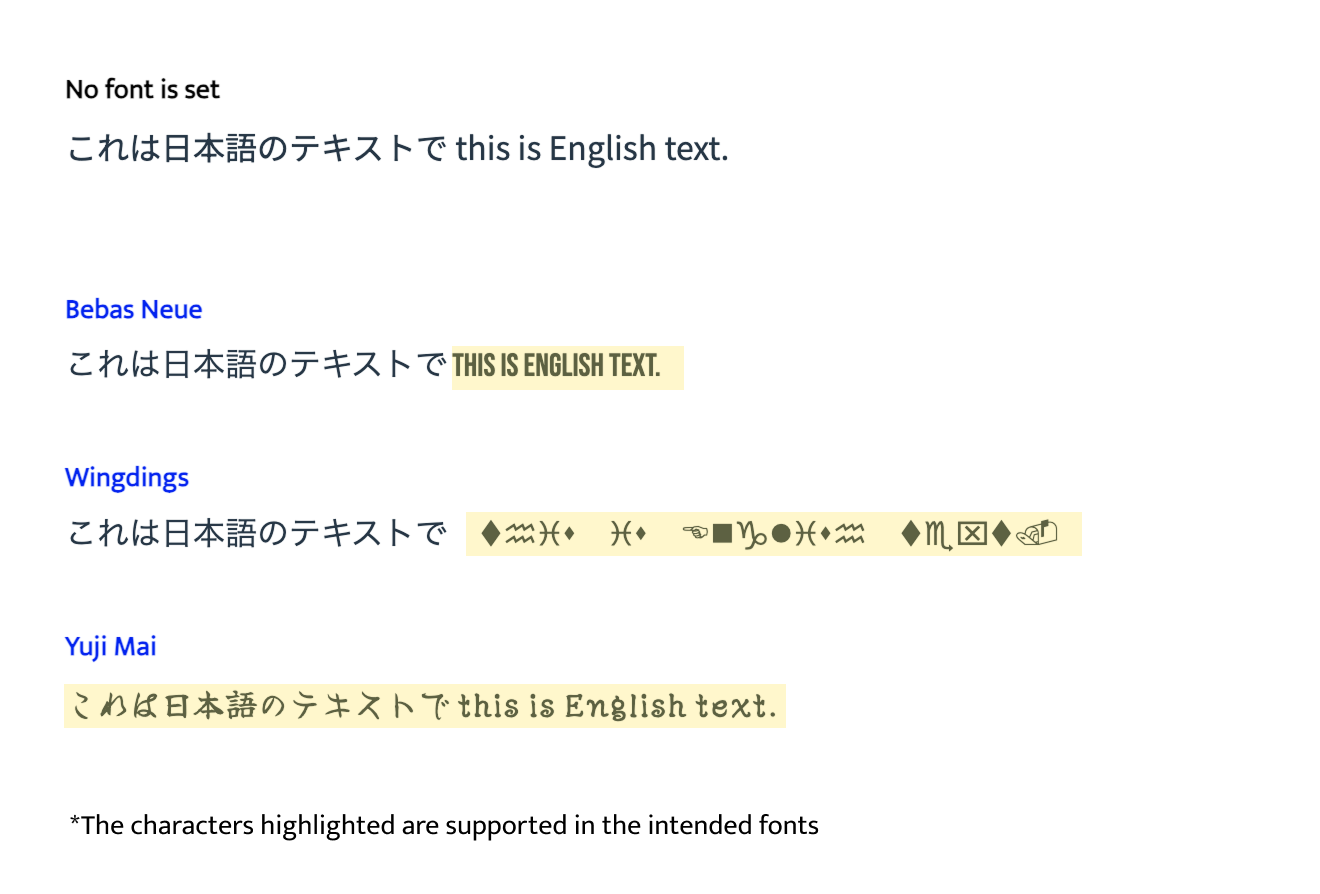

Not every font supports every script. While most Latin fonts work across Western languages, non-Latin languages often rely on unicode characters. If those aren’t supported, the browser falls back to a generic font.

Take a look at the example below. It consists of a paragraph with both English and Japanese text. The fonts Bebas Neue and WingDings do not support Japanese characters and only the English part of the text is rendered in the intended font. In the last example with the Yuji Mai font, note how not only the English characters changed in appearance, but the Japanese characters as well. This is because Yuji Mai is the only font out of the examples that supports both English and Japanese characters.

<!--

No font is set.

English text is displayed in the default generic font.

Japanese text is displayed in the default generic font.

-->

<p>

これは日本語のテキストで this is English text.

</p>

<!--

Bebas Neue is set.

English characters are supported and displayed in the Bebas Neue font.

Japanese characters are not supported and displayed in the default generic font.

-->

<p class="bebas-neue">

これは日本語のテキストで this is English text.

</p>

<!--

Wingdings is set.

English characters are not supported and displayed in the default fallback font.

Japanese characters are not supported and displayed in the default generic font.

-->

<p class="wingdings">

これは日本語のテキストで this is English text.

</p>

<!--

Yuji Mai is set.

English characters are supported and displayed in the Juyi Mai font.

Japanese characters are supported and displayed in the Juyi Mai font.

-->

<p class="yuji-mai">

これは日本語のテキストで this is English text.

</p>

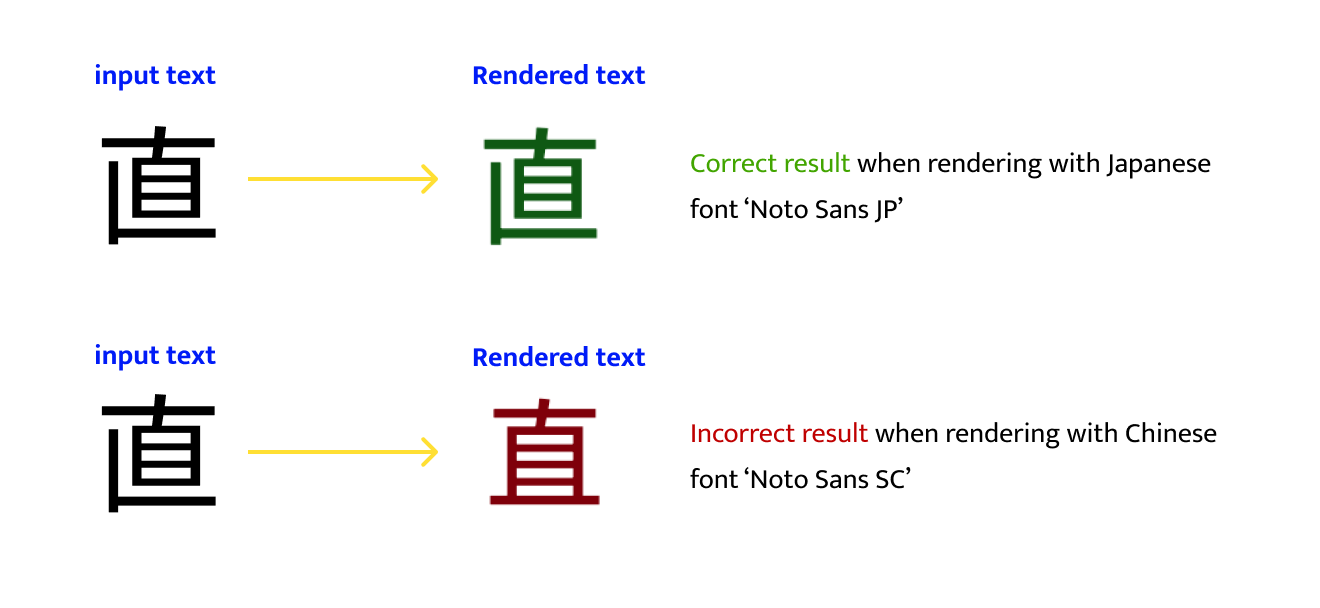

Different languages need different fonts

It’s not just about whether a font supports all the characters in a language. Using the wrong font for a language can make text hard to read or even change the meaning. This is especially true for Asian languages, where characters can have different strokes or shapes depending on the language.

To illustrate this, let’s take a look at the Japanese character of 直 . Note how there are 2 strokes at the bottom, forming a sort of L shape.

<!-- Japanese text rendered in Japanese font (correct) -->

<span class="japanese-font"> 直 </span>

<!-- Chinese text rendered in Chinese font (incorrect) -->

<span class="chinese-font"> 直 </span>

.japanese-font {

font-family: "Noto Sans JP", sans-serif;

}

.chinese-font {

font-family: "Noto Sans SC", sans-serif;

}

When rendering the text with a Chinese font, the bottom left stroke disappears and the ‘L’ shape is no longer visible. To a native speaker, this character has now turned unrecognizable.

💡 Tip: Start with Google’s Noto fonts. They’re designed to support a wide range of scripts and look consistent across languages. Google also offers a good place to start if you want more information on East Asian typography.

Using multiple languages at once with lang

WCAG Success Criterion 3.1.2 requires that parts of a page written in different languages also declare those languages. This is still often overlooked, but beyond accessibility, adding the HTML attribute lang enables you to cater to language specific needs such as line-height and letter-spacing. Additionally, when you use the lang attribute correctly, browser rendering engines can automatically adjust typographic features like ligatures and hyphenation to match the conventions of each language.

Take below code for example:

<p>

これは日本語のテキストで this is English text.同時に使っても問題ない!</p>/* default language is Japanese with below set specifics */

p {

font-family: "Noto Sans JP", sans-serif;

}

This will render great for the Japanese text, but the English text defaults to the fallback font (as discussed in chapter 2) sans-serif and looks slightly small in comparison to the Japanese text in Noto Sans JP.

By adding the lang attribute, you not only improve accessibility, but also unlock the ability to target language-specific styles in CSS without the extra classes or hacks.

<p>

これは日本語のテキストで

<span lang="en">this is English text.</span>

同時に使っても問題ない!

</p>

/* default language is Japanese with below set specifics */

p {

font-family: "Noto Sans JP", sans-serif;

}

/* English text will have another font, color and optmized font-size */

span:lang(en) {

font-family: "Bebas Neue", Arial, sans-serif;

font-size: 1.2em;

color: #001BF7;

}

By simply setting the appropriate lang attribute in your HTML, you ensure that both accessibility and typographic accuracy are maintained for multilingual content.

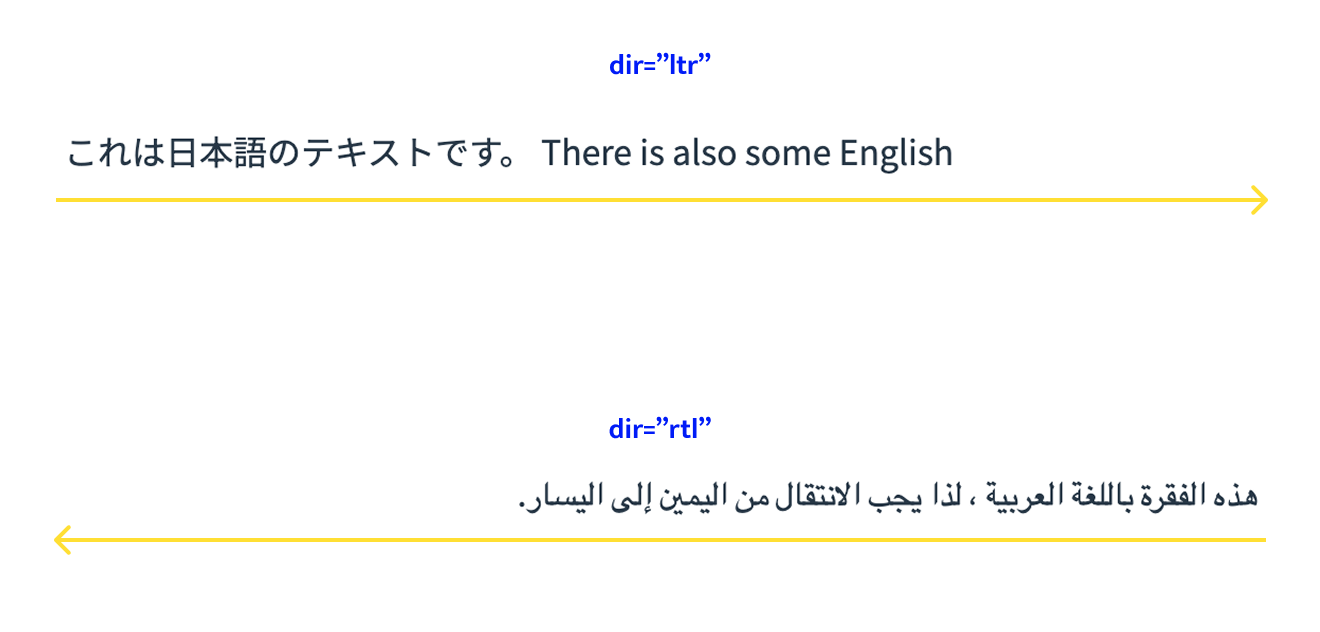

Text direction with writing-mode and dir

Not all languages are written left-to-right (LTR). Arabic, for example, is right-to-left (RTL), and Japanese can be written vertically right-to-left. Thankfully, the web offers some out-of the box solutions such as dir and writing-mode to tackle these cases.

Let’s look at examples for Arabic and Japanese:

<!-- Arabic -->

<p dir="rtl" lang="ar">

هذه الفقرة باللغة العربية ، لذا يجب الانتقال من اليمين إلى اليسار.

</p>

<!-- Japanese with embedded English -->

<p dir="ltr" lang="ja">

これは日本語のテキストです。

<span lang="en">There is also some English</span>

</p>

Here, the dir attribute indicates the directionality of the element’s text.

💡 Tip: note that direction css property exists, but the usage of dir is preferred for accessibility.

💡 Best practice: When working with directional layouts, consider using logical properties like margin-inline and padding-inline etc. instead of physical properties like margin-left. These adapt more naturally to different writing directions.

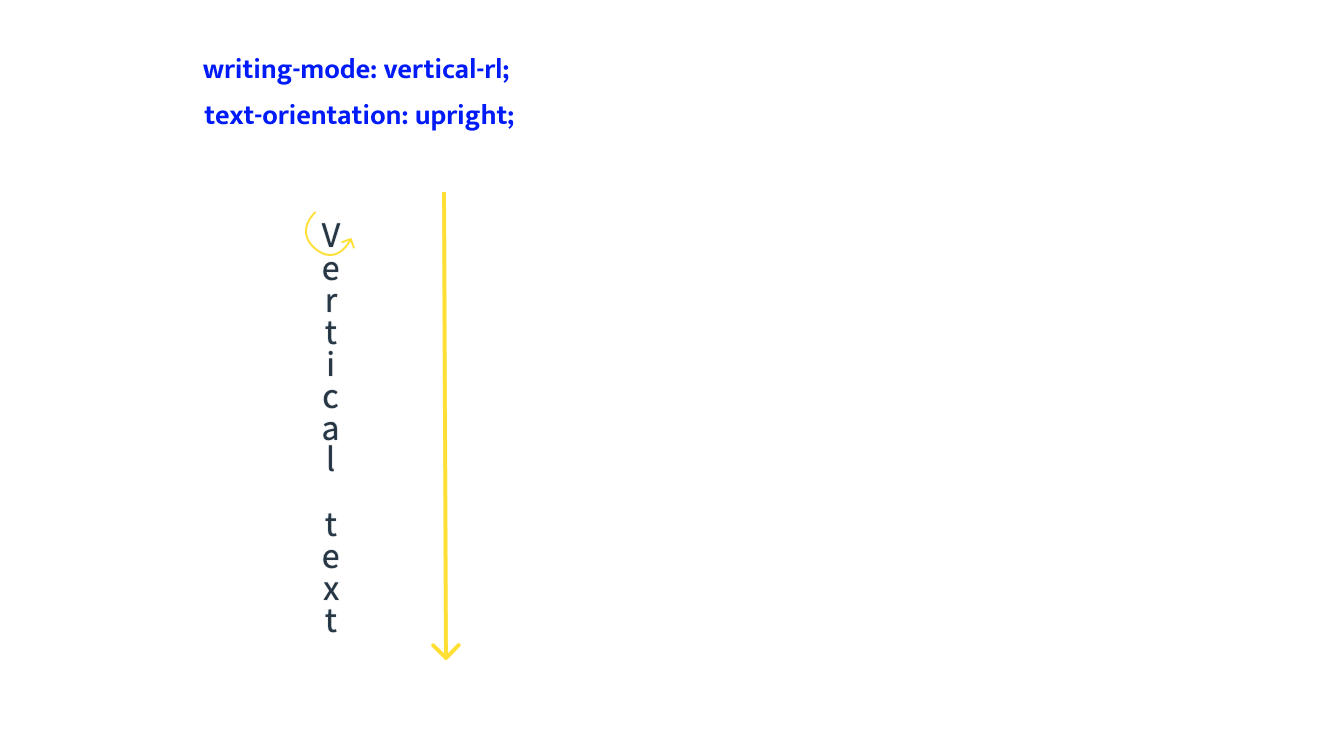

But it is not just about text direction; some scripts are written vertically. One can achieve this using writing-mode.

p {

writing-mode: vertical-rl

}

Well this can be the intended UI in some cases, often one would want the characters themselves to also be rendered vertically. This can be achieved by adding text-orientation

p {

writing-mode: vertical-rl;

text-orientation: upright;

}

Language specific HTML tags such as <ruby>

Some languages require unique mark-up solutions. One of these is the <ruby> tag, which lets you display small text above or beside characters to show pronunciation or meaning. This is used in phonetic languages, such as Japanese and Chinese, to indicate the pronunciation of a character when it is unclear, or the target audience is language learners / younger children with less Japanese knowledge.

<ruby>

漢 <rp>(</rp><rt>Kan</rt><rp>)</rp>

字 <rp>(</rp><rt>ji</rt><rp>)</rp>

</ruby>- rp: Ruby fallback for browsers that don't support <ruby>

- rt: Ruby text element. This is the element that indicates the reading of the characters.

💡 Note: The <ruby> tag has nothing to do with the Ruby programming language.

💡 Fun Fact: Authors sometimes use <ruby> stylistically in novels to create sarcasm, dual meaning or unexpected readings.

Wrapping Up

If there’s one thing I hope more developers take to heart, it’s this: don’t treat non-Latin languages as edge cases.

Before reaching for hacks, remember to:

- Use script-appropriate fonts

- Always specify a lang attribute for each language section.

- Use dir, writing-mode , and text-orientation to reflect the language’s structure.

- Explore language-specific HTML tags like

<ruby>for richer, more accessible content.

Let’s build a better web for everyone, including the 50+ countries that use non-Latin scripts on a daily basis!